Money and Finance

- Links

Graham & Doddsville's Fall 2014 Issue (LINK) The new issue features Wally Weitz of Weitz Investment Management, Guy Gottfried of Rational Investment Group and the team at Development Capital Partners. Additionally, you will find pictures...

- Adam Weiss And James Crichton Of Scout Capital Management To Present At The 7th Annual New York Value Investing Congress

Adam Weiss and James Crichton of Scout Capital Management are scheduled as to present at the 7th Annual New York Value Investing Congress. In their December 2010 interview with Value Investor Insight (currently available as the sample issue HERE), they...

- The Most Important Metric For Dividend Investors

While researching a dividend paying stock should be a holistic process and buying decisions shouldn't be based on any single metric, if there's one metric that every dividend investor should know, it's free cash flow cover. After all, an income...

- Introducing The Dividend Compass

When it comes to equity analysis, a lot of attention is paid to valuation -- and rightly so, as your investing career will likely be a short one if you consistently overpay for assets. Surprisingly, however, there's typically little attention paid...

- Dividend Compass - Royal Dutch Shell

Todd Wenning's Dividend Compass is a diagnostic tool that covers the parts of fundamental analysis most useful to dividend investors. This is a pretty broad set of metrics, Todd describes them here: "Sales growth: Sales are the life-blood of a company....

Money and Finance

Seth Klarman EBITDA Example

From Margin of Safety:

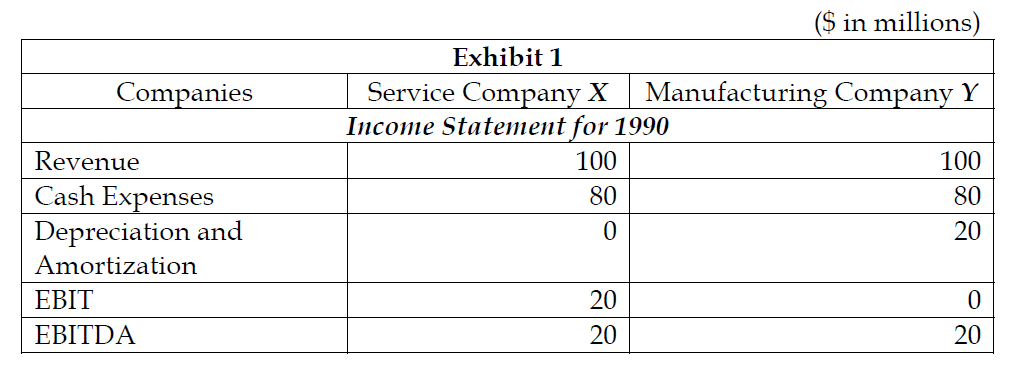

EBITDA Analysis Obscures the Difference between Good and Bad Businesses

EBITDA, in addition to being a flawed measure of cash flow, also masks the relative importance of the several components of corporate cash flow. Pretax earnings and depreciation allowance comprise a company’s pretax cash flow; earnings are the return on the capital invested in a business, while depreciation is essentially a return of the capital invested in a business. To illustrate the confusion caused by EBITDA analysis, consider the example portrayed in exhibit 1.Investors relying on EBITDA as their only analytical tool would value these two businesses equally. At equal prices, however, most investors would prefer to own Company X, which earns $20 million, rather than Company Y, which earns nothing. Although these businesses have identical EBITDA, they are clearly not equally valuable. Company X could be a service business that owns no depreciable assets. Company Y could be a manufacturing business in a competitive industry. Company Y must be prepared to reinvest its depreciation allowance (or possibly more, due to inflation) in order to replace its worn-out machinery. It has no free cash flow over time. Company X, by contrast, has no capital-spending requirements and thus has substantial cumulative free cash flow over time.

Anyone who purchased Company Y on a leveraged basis would be in trouble. To the extent that any of the annual $20 million in EBITDA were used to pay cash interest expense, there would be a shortage of funds for capital spending when plant and equipment needed to be replaced. Company Y would eventually go bankrupt, unable both to service its debt and maintain its business. Company X, by contrast, might be an attractive buyout candidate. The shift of investor focus from after-tax earnings to EBIT and then to EBITDA masked important differences between businesses, leading to losses for many investors.

- Links

Graham & Doddsville's Fall 2014 Issue (LINK) The new issue features Wally Weitz of Weitz Investment Management, Guy Gottfried of Rational Investment Group and the team at Development Capital Partners. Additionally, you will find pictures...

- Adam Weiss And James Crichton Of Scout Capital Management To Present At The 7th Annual New York Value Investing Congress

Adam Weiss and James Crichton of Scout Capital Management are scheduled as to present at the 7th Annual New York Value Investing Congress. In their December 2010 interview with Value Investor Insight (currently available as the sample issue HERE), they...

- The Most Important Metric For Dividend Investors

While researching a dividend paying stock should be a holistic process and buying decisions shouldn't be based on any single metric, if there's one metric that every dividend investor should know, it's free cash flow cover. After all, an income...

- Introducing The Dividend Compass

When it comes to equity analysis, a lot of attention is paid to valuation -- and rightly so, as your investing career will likely be a short one if you consistently overpay for assets. Surprisingly, however, there's typically little attention paid...

- Dividend Compass - Royal Dutch Shell

Todd Wenning's Dividend Compass is a diagnostic tool that covers the parts of fundamental analysis most useful to dividend investors. This is a pretty broad set of metrics, Todd describes them here: "Sales growth: Sales are the life-blood of a company....