Money and Finance

- Hussman Weekly Market Comment: Restoring The "virtuous Cycle" Of Economic Growth

Link to: Restoring the "Virtuous Cycle" of Economic GrowthIn a healthy economy, the productive activity of one sector opens a vent for the productive activity of other sectors of the economy. The useful allocation of resources in one area of the...

- Hussman Weekly Market Comment: Topping Patterns And The Proper Cause For Optimism

Link to: Topping Patterns and the Proper Cause for OptimismNotes to the FOMC The following are a few observations regarding Dr. Yellen’s testimony to Congress. The objective is to broaden the discourse with alternative views and evidence, not to disparage...

- Hussman Weekly Market Comment: Superstition Ain't The Way

“The problem with QE is that it works in practice but it doesn’t work in theory.” - Ben Bernanke, Outgoing Federal Reserve Chairman, January 16, 2014 "When you believe in things that you don't understand, then you suffer. Superstition...

- Hussman Weekly Market Comment: Not In Kansas Anymore

Even in the event that quantitative easing is sufficient to override hostile market conditions in the near-term, it is worth noting that long-term outcomes are likely to be unaffected. We presently estimate a prospective 10-year total return on the S&P...

- Hussman Funds Semi-annual Report

The U.S. economy appears suspended at the boundary between tepid growth and recession, requiring a trillion-dollar federal deficit and unprecedented monetary easing simply to maintain that position. The Federal Reserve continues a well-known and fully-announced...

Money and Finance

Hussman Weekly Market Comment: The Other Side of the Mountain

Link to: The Other Side of the Mountain

The financial markets are at a transition that reflects tension between two realities. The first is that the Federal Reserve’s policy of quantitative easing has driven the stock market to valuations associated with the most extreme speculative peaks on record, coupled with a fresh boom in initial public offerings – with companies having zero or negative earnings accounting for three-quarters of new issuance – and record issuance of “covenant lite” leveraged loans (loans to already highly indebted borrowers, lacking normal protections that mitigate losses in the event of default). The other reality is that unconventional monetary policy has done little to push real economic activity or employment past the border that has historically distinguished expansions from recessions (about 1.8% year-over-year growth in both real final sales and non-farm payroll employment).

There is no question that quantitative easing has supported the mortgage market, and was almost wholly responsible for that role in late-2008 and 2009. But QE is not what ended the financial crisis (the March 2009 change in accounting rule FAS 157 is what removed the risk of widespread bank failures). Any economist familiar with the work of Nobel laureates like Milton Friedman or Franco Modigliani, or simply with decades of economic data, could have predicted even in 2010 that Bernanke’s efforts at creating a “wealth effect” would have weak effects on consumption, job creation and economic activity. In order to get any meaningful overall effect, it was clear that the Fed would have to create enormous but ultimately temporary distortions, inviting risk of longer-term financial instability. The Fed has now done exactly that.

.....

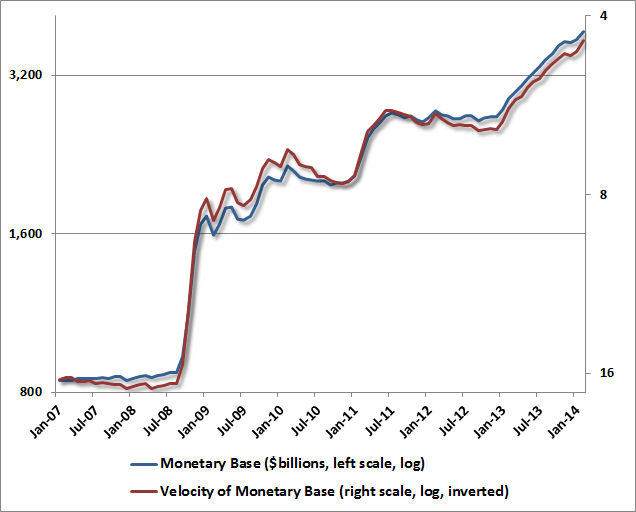

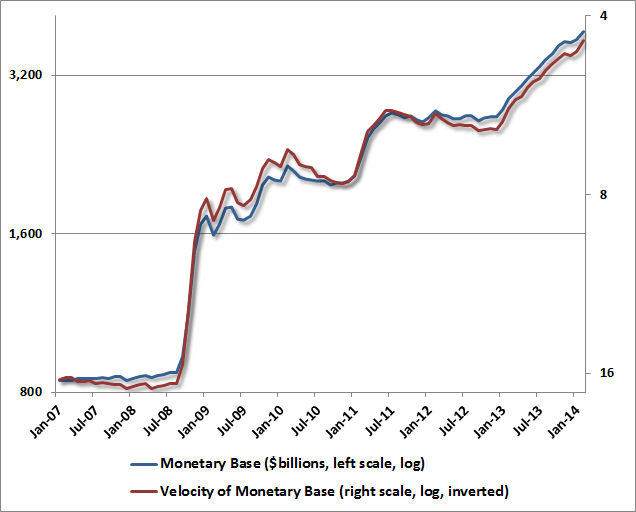

Meanwhile, like any policy that creates risk and distortions without reliable effects, more QE isn’t the answer to anything – not even if economic growth were to weaken, not even if inflation was to slow further, and not even if the equity markets were to decline substantially. Among the many problems with quantitative easing, an important feature is that monetary velocity falls in almost exact inverse proportion as the monetary base expands. In other words, regardless of the quantity, the new monetary base simply sits idle. Regardless of effects on financial speculation, there is almost precisely zero effect on economic activity – not on prices, not on real GDP, not on nominal GDP.

In order to increase monetary velocity without proportionally reducing the monetary base, we would have to observe exogenous upward pressure on interest rates. That’s likely to emerge in the back-half of this decade, though probably after an intervening economic slowdown. At that point, fairly early into the next expansion, the Fed is likely to stop hoping for higher inflation and discover it instead to be the last thing it wants. Until then, the Fed would provide the greatest benefit to long-run economic prosperity simply by ceasing its insistence on harming it by promoting speculation in efforts to offset short-run cyclical fluctuations.

- Hussman Weekly Market Comment: Restoring The "virtuous Cycle" Of Economic Growth

Link to: Restoring the "Virtuous Cycle" of Economic GrowthIn a healthy economy, the productive activity of one sector opens a vent for the productive activity of other sectors of the economy. The useful allocation of resources in one area of the...

- Hussman Weekly Market Comment: Topping Patterns And The Proper Cause For Optimism

Link to: Topping Patterns and the Proper Cause for OptimismNotes to the FOMC The following are a few observations regarding Dr. Yellen’s testimony to Congress. The objective is to broaden the discourse with alternative views and evidence, not to disparage...

- Hussman Weekly Market Comment: Superstition Ain't The Way

“The problem with QE is that it works in practice but it doesn’t work in theory.” - Ben Bernanke, Outgoing Federal Reserve Chairman, January 16, 2014 "When you believe in things that you don't understand, then you suffer. Superstition...

- Hussman Weekly Market Comment: Not In Kansas Anymore

Even in the event that quantitative easing is sufficient to override hostile market conditions in the near-term, it is worth noting that long-term outcomes are likely to be unaffected. We presently estimate a prospective 10-year total return on the S&P...

- Hussman Funds Semi-annual Report

The U.S. economy appears suspended at the boundary between tepid growth and recession, requiring a trillion-dollar federal deficit and unprecedented monetary easing simply to maintain that position. The Federal Reserve continues a well-known and fully-announced...